German Wine

Terms

The German wine laws,

revised in 1971

to bring them closer in line with those of other members of the EU,

divided the

wine into two classes: Table Wine and Quality Wine -

This is not just for Riesling, it can apply to other German Varietals.

Table Wine is divided into two

categories: Deutscher

Tafelwein (lowest category) and Landwein (introduced in

1982 and

equivalent to French Vin de Pays) - It is rare to find these

wines in the US.

Quality Wine (Qualitätswein) is also

divided into

two categories: Qualitätswein bestimmer Anbaugebiete (QbA)

and Qualitätswein

mit Prädikat (QmP)

QbA wines are produced from one of 13

regions

(which must appear on the label) and will generally be chaptalized

(must

enrichment before or during fermentation to increase level of alcohol

and/or

sweetness).

Note: QbA wines may NOT have had

any sweetness added, and may infact qualify as a QmP wine as below,

however the winemaker may not want the hassle of meeting the criteria

(law) and doing the paperwork. There are many winemakers now that wish

to abandon the 1971 QmP regulations all together....

QmP wines are those "with special

attributes" and also come from a single one of the 13 regions (also

appearing on the label) and from a single bereich (district).

Chaptalization

is

forbidden, although they may be sweetened with Süßreserve (sterile

unfermented

grape [same grapes] must added before bottling to increase sweetness

and balance

acidity).

To further complicate matters, QmP wines

are

divided into six styles (Prädikate) based on initial must weights in

ascending

order: Kabinett, Spätlese, Auslese, Beerenauslese (BA), Eiswein and

Trockenbeerenauslese (TBA).

Kabinett - most delicate,

crisp acidity,

green

apple and citrus

Spätlese - literally

"late-harvest," more

body than Kabinett, riper fruit flavors, no green apple and perhaps

tropical

fruit (mango and pineapple).

Auslese - from individually

selected

extra-ripe

grapes; highest level of Pradikat to appear commonly as a dry wine; can

be a

richer, sweeter, riper Spatelese or very sweet, showing botrytis

character.

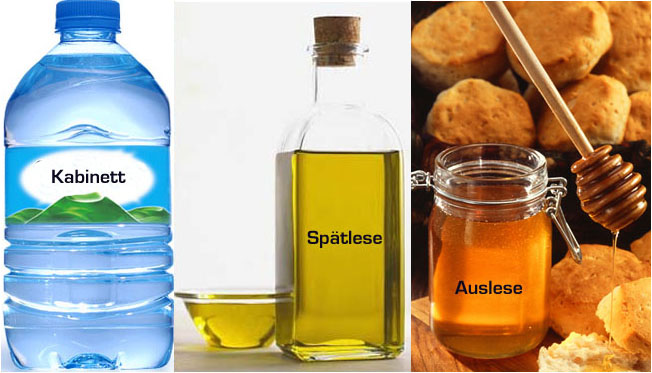

The above 3 are the most commom

QmP wines and while the below image is perhaps an oversimplification,

it does give you an idea of the theorhetical differences in viscosity

---

Beerenauslese - rare expensive

wine made

from

individually selected grapes, ideally with botrytis; a sweet

wine with

exhilarating complexity and refreshing acidity.

Eiswein - literally

"ice-wine," left on

vine to ripen to sugar levels of BA and picked when temperature is

below -8

degrees C; pressed after frozen water removed, producing a wine with an

intriguing contrast of richness, acidity and great fruit purity.

Trockenbeerenauslese -

produced in minute

quantities and only in the finest vintages from individual botrytised

grapes

that have shrivelled to be tiny raisins; sugar level will yield a potential

21.5% abv but will be matched with high acidity levels; actual level

after

fermentation of abv will rarely excede 8%.

And just when you think you have everything

sorted out,

here are a few additional terms that might appear (in addition) on the

label:

Trocken - Very Dry - Germans

love Trocken - probably in reaction to the sugar-water Liebfraumilch

that Germany is known for and they hate.

Halbtrocken - Dry - Use

is becoming less common

Classic - "Harmoniously dry"

with minimum

12% abv (11.5% in Mosel-Saar-Ruhr); must be made from a single varietal

from a

single vintage in a single region (all appearing on label)

Selection - At least Auslese

ripeness

levels

(potential 12.2% abv) from a individual vineyard site (appearing on

label)

Erstes Gewachs, Erstes Lage

&

Grosses

Gewachs - Riesling (or Pinot Noir) from one of the recognized

top-quality

(first growth or Premier Cru) Einzellagen (vineyards); subject

to a

number of requirements including a stringent taste test See VDP

Other German Wines:

Not as popular as Rieslings

are German

Pinots, but they are on the move. Germans being as precise as they are

call these Burgundies or

Burgunders.

Weisser Burgunder is a Pinot Blanc

Grauer Burgunder is a Pinot Gris

Spät Burgunder is a Pinot Noir

Müller-Thurgau

is a ‘light’ Riesling - mostly forgettable

Silvaner is a white grown mostly in Franconia in limestone soil.

Blauer Portugieser is a red from Portugal (1700s) , oak casks are used.

Dornfelder is a Sweetish Red Wine

with high to medium

tannins

from:

Astor Wines Newsletter : German Wines Intro

Germany is a land of contradictions and extremes. Nowhere in the vinous world can one find wines so sweet and lush from vineyards so bitter and harsh. (Well, perhaps not literally, but these places sure aren’t for the novice grape-picker.) Germany’s vineyards rely upon the warming influences of the nation’s myriad rivers in order for the grapes to endure the brutally cold winters and ripen properly. In fact, Germany’s viticultural regions almost all take their names from the respective rivers that nurture the invariably steeply terraced hillside vineyards.

Many people today think of German wine as virtually synonymous with the noble Riesling grape, but in fact Germany is home to a wide range of other varietals. Admittedly, none of them even approach Riesling’s level of grandeur, but they exist nonetheless: Silvaner, Scheurebe, Spätburgunder (aka Pinot Noir), Grüner Veltliner, Portugieser (aka Blauer Portugieser, if that helps), Müller-Thurgau, Lemberger, Grauer Burgunder, Weisser Burgunder (aka Pinot Blanc), Gewürztraminer…to name but a few.

While each region has very distinctive wines, the country is united under the rather strict German wine laws, last revised in 1971. With prototypical German precision, a rigorous scale was instituted by which each wine is classified according to the amount of sugar in the grapes at the time of harvest.

At the very bottom of the scale, one finds simple “Tafelwine” (aka table wine) made from the least ripe grapes as well as from grapes from unapproved regions and varieties. This accounts for but a minuscule portion of Germany’s total wine production. All other wine falls into a category known as “Qualitätswein Bestimmter Anbaugebiete” – or, more simply, QbA (bless the Germans for their affinity for acronyms). And then, within this category, there is a subset of still higher quality wines, called “Qualitätswein mit Prädikat”, or “quality wine with distinction”, (QmP for short). Wines made from progressively riper grapes fall into distinct tiers on the QmP scale. Those tiers are, in order of ascending ripeness: Kabinett (meaning “reserve”), Spätlese (meaning “late harvest”), Auslese (meaning “select harvest”), Beerenauslese (meaning “berry select harvest”), Trockenbeerenauslese (meaning “dried berry select harvest”), and Eiswein (meaning “ice wine”).

While these classifications speak to the degree of ripeness at the time of harvest, they do, generally, correspond to the resultant level of sweetness in the wines as well. There are, of course, some exceptions. For example, some Spätlese wines are vinified dry or half-dry (indicated by the term “trocken” or “halbtrocken” on the label). These wines have significantly higher percentages of alcohol – closer to the typical 12-13% seen elsewhere in the world. This brings us to one clever tactic for deciphering German wine labels: the lower the percentage of alcohol, the higher the residual sugar (and hence the sweeter the wine). If a wine has only 6-8% alcohol, that means a whole whopping lot of the initial grape sugar remains unfermented in the wine; if it’s 12% or higher, then virtually all of the grape sugar has been converted into alcohol, and hence the wine is dry. The latter three tiers of QmP wines (BA’s, TBA’s, and Eisweins) are invariably dessert-level in sweetness, with Ausleses usually just straddling the fence.

While we tend to associate Germany with sweet wines (and the classification above serves to reinforce that notion), Germany has always produced exceptionally fine dry and nearly dry wines. In recent years, there have been numerous efforts to re-establish the primacy of these long neglected bottlings. So if sweet wines aren’t your cup of tea, don’t be too quick to write off Germany; keep your eyes peeled for those lovely Trocken wines the next time you’re in the market for a crisp, dry white.

As one can imagine, creating a vintage chart for such a large and varied wine producing country is fraught with trouble and inconsistencies. But, in an effort to at least minimally arm you with information for Tuesday’s shopping spree, here are a few things to bear in mind:

Both 2003 and 2005 were exceptionally warm vintages, and as such the grapes achieved unusually high levels of ripeness. If you’re looking to test out a sweeter style of wine, these are the vintages to seek.